October 27, 2016

SVSU serves as steward to 19th century photos important to histories of Saginaw, black Americans, and photography itself

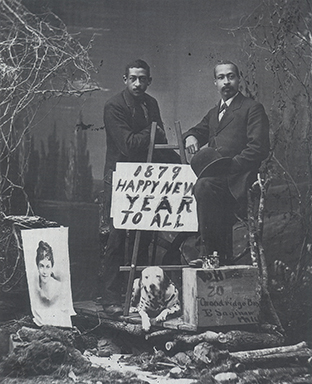

A black top hat balanced on his raised right leg, Wallace Goodridge rests his left forearm atop the same wooden easel where his brother, William Goodridge, is perched in a similar pose, inches away. Together, in the Saginaw photo studio they own, the siblings stare forward at the camera. Each awaits the telltale signs that indicate a photograph has been taken. Prop foliage surrounds them. A canvas in the background portrays a painted wooded landscape. A Dalmatian rests lazily at their feet. The easel between the brothers hoists a sign, and it bears a message:

A black top hat balanced on his raised right leg, Wallace Goodridge rests his left forearm atop the same wooden easel where his brother, William Goodridge, is perched in a similar pose, inches away. Together, in the Saginaw photo studio they own, the siblings stare forward at the camera. Each awaits the telltale signs that indicate a photograph has been taken. Prop foliage surrounds them. A canvas in the background portrays a painted wooded landscape. A Dalmatian rests lazily at their feet. The easel between the brothers hoists a sign, and it bears a message:

“1879 Happy New Year To All.”

Wallace and William Goodridge are not alive now, to say the least. They died more than a century ago. Yet the nearly 140-year-old photograph that froze their moment in time together in 1879 breathes with life today.

For one, their late-19th century camerawork produced an image stunningly vivid in detail, allowing modern eyes to see its story told in past or present tense. Secondly, the story of this particular family in this particular portrait carries historical significance that endures to this day. Historians have chased this story. They still are.

John Jezierksi began his chase decades ago. The effort landed a copy of the New Year’s Eve photograph — along with dozens of other compelling pictures produced by the Goodridge brothers — in the secured archive room on the first floor of SVSU’s Zahnow Library. There, the university serves as a steward to a legacy that touches on Saginaw history, photography history, black history, and American history, all at once.

*

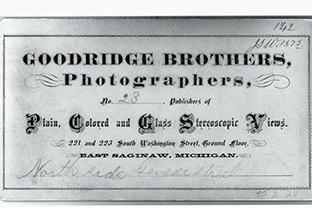

Jezierski, who retired in 2006 as an SVSU professor of history, recognized the power of the Goodridge brothers’ legacy almost immediately upon arriving in the region in 1970 to begin his career with the faculty. While teaching and researching Michigan history, he was exposed to images of Saginaw and its people, dating back to the community’s booming white pine lumber industry days. Many of those pictures were credited to the Goodridge brothers, who successfully operated as professional photographers from 1847 to 1922.

Jezierski, who retired in 2006 as an SVSU professor of history, recognized the power of the Goodridge brothers’ legacy almost immediately upon arriving in the region in 1970 to begin his career with the faculty. While teaching and researching Michigan history, he was exposed to images of Saginaw and its people, dating back to the community’s booming white pine lumber industry days. Many of those pictures were credited to the Goodridge brothers, who successfully operated as professional photographers from 1847 to 1922.

“I kept coming across these photographs linked to this one family, but there wasn’t a whole lot of information about them,” says Jezierski, who lives in Portland today. “Their photographs were so compelling. I had to know more.”

So he spent years reading through newspaper articles about the siblings while researching their photo collection. Jezierski then wrote a biography on the brothers, “Enterprising Images,” published in 2000.

The 368-page book chronicles the 75-year span of their photography businesses, which began with a third brother in their hometown of York, Pennsylvania, and continued in the Saginaw region in 1863, when Wallace and William Goodridge relocated there. “Enterprising Images” also highlights their international acclaim, which included the inclusion of their photography in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s exhibit at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris.

“Their work was significant on many levels,” Jezierski says.

For one, photography was in its infancy when the Goodridges opened up shop in 1847. The earliest known photograph to include people was produced less than a decade earlier. So the Goodridges weren’t simply creating the first photos in their communities’ history. They were creating some of the first photographs of communities in history.

What made this feat especially impressive was the color of their skin. They were a black family that began operating a successful company 18 years before the U.S. Congress passed the 13th Amendment, which freed black slaves across the country.

The Goodridges avoided enslavement. They were born to the free son of a black slave woman and a white man, and lived in northern states that abolished slavery decades before the amendment did so nationally. Regardless, racial divides remained wide and violent during the years the brothers prospered. The final Goodridge photo, after all, was produced nearly a half-century before the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

“They managed to succeed in a very difficult world,” Jezierski says. “They did it without emphasizing their heritage. Many early black photographers photographed black people and culture. The Goodridge brothers succeeded by serving the white community, too.”

Still, the siblings contributed substantially to a movement meant to humanize blacks at a time when blacks often were treated as less than human, says Deborah Willis, an award-winning author considered one of the nation’s leading historians on black photography.

Willis, chair of the Department of Photography & Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, first researched the Goodridge brothers in the 1970s. In their images of black families, she recognized an answer to a call for action from Frederick Douglass, a slave-turned-social reformer and one of the most influential black voices of the 19th century.

At the time, many photographs portrayed blacks poorly, sometimes in images where they posed while performing slave work or stealing from whites. Douglass, concerned about how such imagery was influencing the nation’s perception of blacks, called on blacks to “arm themselves in the war of images,” Willis says.

“Frederick Douglass believed photography was biography, and if you look at a photograph, you can see a person’s character,” she says.

The Goodridge brothers’ photos of blacks — including their self-portraits — showed them in the same dignified manner displayed in many photos of whites at the time.

“You found real joy in those images; a real understanding of the importance of family life, and the importance of documenting it,” Willis says.

“When they began to take pictures of themselves and put them into photo albums to show to their family members, that’s a real light bulb, ‘ah-ha’ moment where you understand a representational system in action.”

*

These days, Rose San Miguel oversees the Goodridge catalog in Zahnow Library. Occasionally, the SVSU archives specialist, out of curiosity, opens the emerald green cover of the photo album that protects those images of 18th century family portraits, lumberyard scenes and early Saginaw.

These days, Rose San Miguel oversees the Goodridge catalog in Zahnow Library. Occasionally, the SVSU archives specialist, out of curiosity, opens the emerald green cover of the photo album that protects those images of 18th century family portraits, lumberyard scenes and early Saginaw.

“It’s fascinating to see what life was like around here back then,” the SVSU archives specialist says. “With a lot of these pictures, it’s amazing what kind of detail there is.”

The daguerreotype-style photos are copies Jezierski collected during his book research. He later donated the photos and his notes to the university archives, which house mementos of the region’s rich history as well as materials and research papers from students and faculty of the past and present.

“There’s a lot of history in this room,” San Miguel says. “It’s important that we keep these items safe and secure. It’s an important role we sometimes play for the community; preserving its history.”

Sometimes that role extends to sharing the history. New York City-based filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris used the Goodridge brothers’ work stored in Zahnow Library as part of his film, “Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People.” The documentary aired on PBS in February 2015 as part of the Independent Lens film series. It remains available online and in Zahnow Library’s DVD collection.

The movie explores the role of photography in shaping the identity, aspirations and social emergence of blacks throughout history. Willis is featured in an interview, discussing the Goodridge family’s contribution to that history.

The photo of Wallace and William Goodridge on New Year’s 1879 makes an appearance in the film, too, providing imagery as Willis describes how the brothers helped open the eyes of a nation to the new world of photography and a new way of thinking about their fellow man.