October 29, 2015

Showing of Rocky Horror Picture Show Leads to Riot 1979

It has almost become tradition for theatres to run the 1975 movie, The Rocky Horror Picture Show around Halloween. With the holiday two days away, the following is an excerpt of a story from the Spring 2010 Reflections magazine, titled "Snowballed at SVSU, 12-04-79."

It has almost become tradition for theatres to run the 1975 movie, The Rocky Horror Picture Show around Halloween. With the holiday two days away, the following is an excerpt of a story from the Spring 2010 Reflections magazine, titled "Snowballed at SVSU, 12-04-79."

Freshman Liz Virgin had seen the flyers. Papers were all over campus about the film to be shown that night, offering a dose of escape with crimson floating lips and the words:

“A different set of jaws”–The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

By 10:15 that night, more than 250 people had flocked to the cafeteria to see The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The film was a low-budget cult classic based on an often-run musical, and, over the years, audiences had spawned a series of rituals. When a wedding scene came, for example, viewers were expected to toss rice; when a man at a dinner mentioned giving a toast, viewers lobbed burnt bread.

That night, a fraternity made a fundraiser of it and sold both rice and toast to the masses.

Billy Dexter, a freshman, had joined his friends for the movie. The lights dimmed and the movie began, but things didn’t play out how he’d thought they would.

What played was pandemonium. Rice that was supposed to be pulled from its bags instead shot across the room as plastic-wrapped missiles. And people lacked the patience to await an onscreen toast before casting what they had on their classmates. Soon many items were fired through the air: food, drinks, salt shakers, pepper containers and, according to reports, even chairs.

Organizers repeatedly stopped the film, asking viewers to please calm down. But students’ mischief couldn’t be caged, and ultimately the affair lasted just 22 minutes.

All involved were asked to return to their rooms.

By the time Campus Safety showed up, the floor was coated with debris. Seats and tables had been toppled. A Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity brother named Steve Umphrey had assisted in planning the event and was consequently cleaning it up.

The students had gone outside, many of them gathering in the clearing between the dorms.

That’s where the real trouble would soon begin.

The Real Trouble Begins

Sometime after midnight, a telephone rang in the darkened home of a county sheriff. The man would awaken and be told of the reports. Some 150 Iranian students had “taken over” part of Saginaw Valley’s campus, the caller said, and they had “destroyed a building.”

In the snow-covered clearing flanked by brown-brick dormitories, about 75 students were running around, squirting water guns at each other, throwing snowballs.

Officers tried to reason with them. After much coaxing, the students complied; within an hour, all had retreated to their dorms. Officers, satisfied that order had been restored, left the courtyard to find warmth. And within two minutes of the solace, a dorm door reopened. A young man shot outside and began to yell. Suddenly, other doors popped open, and students rushed out and joined in.

Soon the snowball fight began anew.

Mike DuCharme, a sophomore, was in his room working on a paper. Looking out the window, he noticed in the distance a quickly moving line of blue lights. Wondering if there had been an accident at the airport, he kept his eyes on them. Then he realized they were coming closer.

Police Lose Control

He went downstairs and reached a window in time to see one of the patrol cars skidding on icy pavement. The cruiser slammed into a lamppost, knocking it to the ground.

Out in the courtyard, more police officers had arrived in riot helmets, carrying nightsticks. Some students ran away from the cops; others just hurled snowballs at them.

From somewhere in the melee, Billy Dexter and three roommates made it back to their suite. Still giddy from the experience, one pulled open the window and jeered at the cops on the ground below. Instantly, five officers looked up and raced for the stairs.

Students Jailed

Later that night when Billy called his mother, she thought his story was a practical joke. Billy had grown up in inner city Detroit and kept his record clean before coming to Saginaw Valley, a school in the middle of cornfields — and now he was calling her from jail?

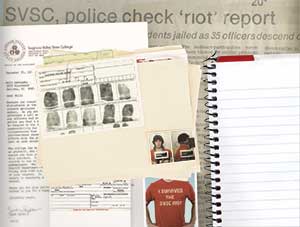

But inside two locked cells at the Saginaw County jail were the 53 people arrested — 44 males and nine females — one non-student, two commuters and 50 dorm residents. (And rumor had it that the young women shared their seven hours in the cell with an accused murderer.)

Apparently, many made the best of it. While in jail, students started singing; and they sang so loudly that the jail staff threatened to hose them down.

Steve Zott, star quarterback on the football team, used his call to phone “Muddy” Waters. The football coach and athletic director had recently returned from a game in South Carolina. With the leftover money on hand from the trip, he ventured down to the jail himself.

By then, eight students had parents come to bail them out. The bond for the other 45 — a $1,025 price tag — would be covered by the university.

By 7:45 Wednesday morning, the last students were being transported in vans back to campus.

In its next issue, The Valley Vanguard published an editorial interpreting what factors had contributed to the events that night: overloaded dorms, pent-up frustrations, looming exams and cafeteria food. The movie, according to the piece, provided a fun outlet for students’ energy. When it prematurely ended, they sought an alternative.

Later, T-shirts sprang up around campus that read, “I SURVIVED THE SVSC RIOT” — thanks to the pluck of a budding entrepreneur. Billy remembers the way people treated the 53 jailed survivors: “We were pretty popular around campus after that,” he says now, laughing.

Radio Reports Inaccurate

Inquiries later resulted in the radio transmissions from that night being made public. At 11:43, an officer called in to Central Dispatch: “Situation we have is about 150 ‘disorderlies.’ They literally destroyed one building, and we’re waiting for help before we take any other of them.”

Word was passed along. Central told Saginaw Police, “They totally destroyed one building.” Eight cars were sent, including a vehicle with lieutenant and a sergeant. At 11:51, Central told its Bay County counterpart “they totally demolished one building.”

Media agencies would descend on the campus. The Saginaw News called the incident SVSC’s “own horror show,” adding that “officers swept onto the campus amid rumors of Iranian involvement and calls picturing a building under siege.”

Subsequent hearings would find reason to suspend two students from the dorms and one from the college. Many others would receive letters of apology from the school’s administration.

SVSU’s crisis that night would compel the Board of Control at its May 7, 1982, meeting to pen a resolution that allowed the college to deputize the officers in its public safety department.